During

World War I the experiences of soldiers on the Western and Eastern fronts

were dramatically different. While the West was dominated by industrial

warfare, mud, and trenches, soldiers in the East found themselves in huge,

evacuated territories, far away from anything familiar to them. Before this

conflict, most people outside of Click on the map to

see the details The War

at Home The

outbreak of the war in August 1914 was met with mixed emotions in the

Northern Baltic region. In Throughout

the Russian Empire, the war thrust itself into the lives of millions. The

first resistance to German belligerence came about in the formation of nine

regiments of Latvian Riflemen (discussed further below). About 100,000

Estonian men – close to 10% of the ethnic population – were conscripted into

the Tsarist armed forces. (Raun, p. 95) Despite the

fact that Latvian national troops had been incorporated in July 1915, no

parallel Estonian or Lithuanian divisions were created before the February

Revolution in 1917. There had been a predilection by Estonian political

leaders to establish national units, nonetheless

fear of simply making the situation worse prevented any such developments at

the time. Although Grassroots

Experiences In the

eyes of the common people of

Greene’s

accounts tell of a Lithuanian Countess and her family who endured three and a

half years of German occupation:

Prussian soldiers clicked about the manor house, German

Soldiers were billeted in the barns. No mail, no newspapers;

we were completely cut off from the world. So far as

we

knew, Justifiably,

the Countess questioned her families, as well as her country’s future. Her

main concern appeared to revolve around what the Allies would ultimately do

with the region. Create an independent The

Countess described the emergence of an organization developed for

self-protection called the Green Guards. They named themselves as such in

order to be distinguishable from the Reds – the revolutionary troops – and

the Whites – the anti-revolutionary soldiers. The Green Guards were created for

defense of the village; when White or Red guards came into the area the Green

Guards drove the cows into hiding places in the swamps and then hid in the

woods to snipe the enemy when they started to plunder. The

following is the story of Khaim Kusilovish,

of the Another

eyewitness account is from the Latvian

Soldiers As a part

of the Russian Empire at the onset of the First World War,

The

Latvian Riflemen set themselves apart from other units through discipline,

fighting capabilities, educational and cultural levels, and most importantly

by their heroism, which arose from a foundation of faith in freedom and

independence of

German

Occupation: Verkehrspolitik & Kultur Military

triumphs in 1914 and 1915 brought the German armies into possession of the

territories along the The

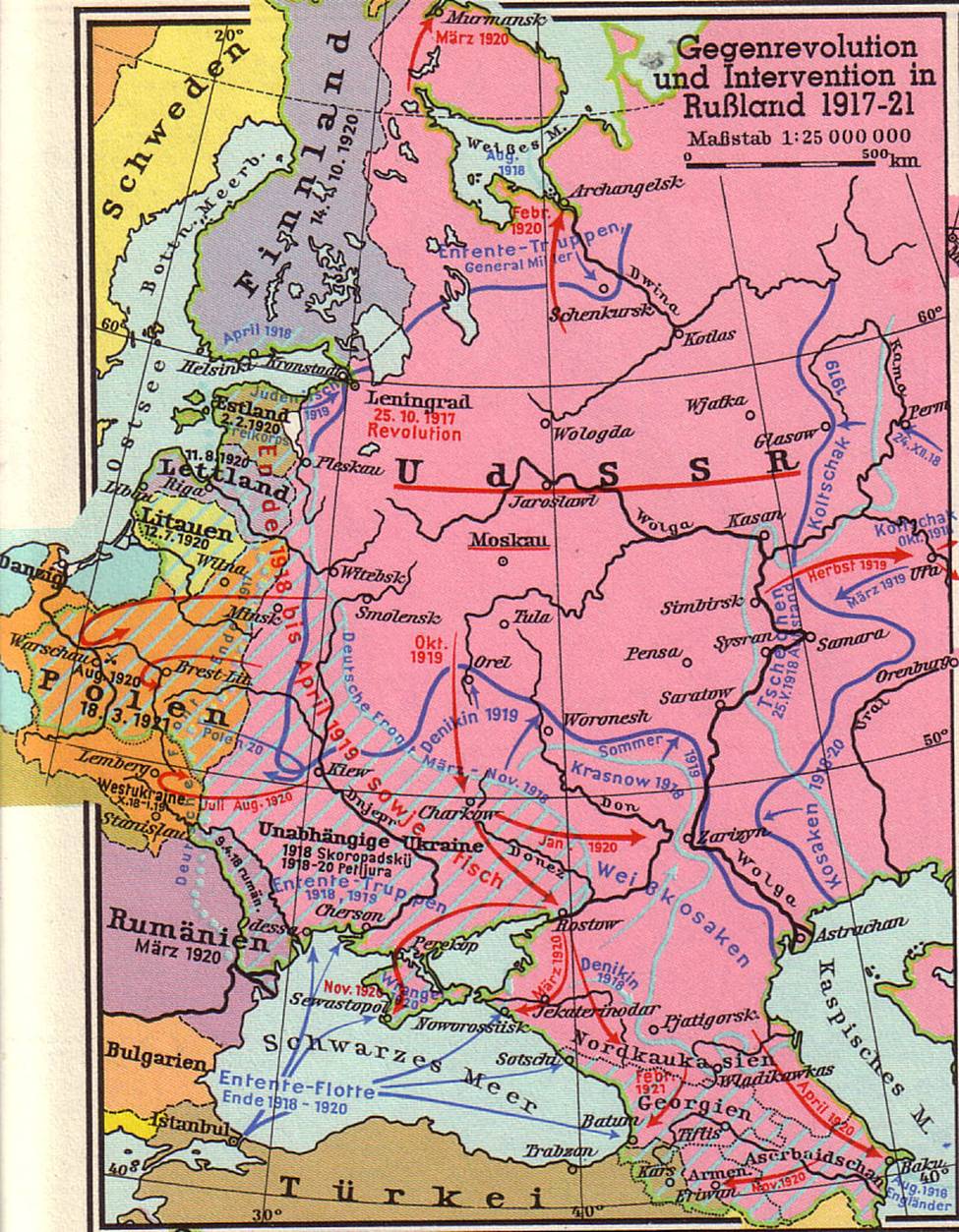

October Revolution forced the Russian army out of the war, resulting in the

Armistice of December 1917. The ensuing Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on March 3,

1918 established peace between As

natives were not allowed to move between the official boundaries, this

created obvious hardships. The borders were often established without any

consideration given to existing patterns of settlement of social organization.

Natives could not travel to visit relatives or friends, and traveling Jewish

merchants lost their livelihood entirely. Military courts inflicted huge fines,

penalties and even confiscation for violations. There was

also a cultural counterpart to the ‘movement policy.’ While Verkehrespolitik controlled the land, borders, and

movement, Ober Ost’s command

aimed, through a process called Kultur, to transform

the identities of the different native populations, essentially trying to

impose a new culture where ‘uncivilized’ peoples would be ameliorated by

German ‘genius.’ Considering the area’s ethnic diversity, this was a rather large

objective, which involved, more or less, reinventing their culture. Ober Ost’s cultural policies

had three aims. First, they wanted to put forth an impressive image of the

state and it’s civilizing effect in the East.

Second, native culture was to be infused with German institutions, which

would redefine their identity and guide their development. Finally, they also

aimed to provide German soldiers with a sense of their mission. Regardless

of these objectives, arrogant, overreaching ambitions brought constant

conflict between the seemingly utopian ends and barbarous practices of the

state’s policies. Instead of successfully molding the native peoples to

German ideals, what resulted was an outburst of native resistance. Throughout

the implementation of German Kultur, the native Baltic

peoples had come to recognize and embrace the individual characteristics of

their own cultures. A feeling of nationalism sprung from these realizations

and a renewed sense of vigor spread throughout the region.

War Beyond

November 11, 1918 Collapse

of the ‘German Order’ in 1918, after an almost assured victory in the east,

was beyond comprehension for the soldiers of Ober Ost. Humiliation, frustration, and regret caused a

feeling of fury, which was then aimed at the East and its inhabitants. The

resulting group of German Freikorps unleashed their

hatred as well as their refusal to accept defeat on the Baltic lands after

the war. Contrary to popular belief, World War I did not end precisely in

November 11, 1918, but continued through acts of violence let loose from a

group of people who refused to accept defeat.

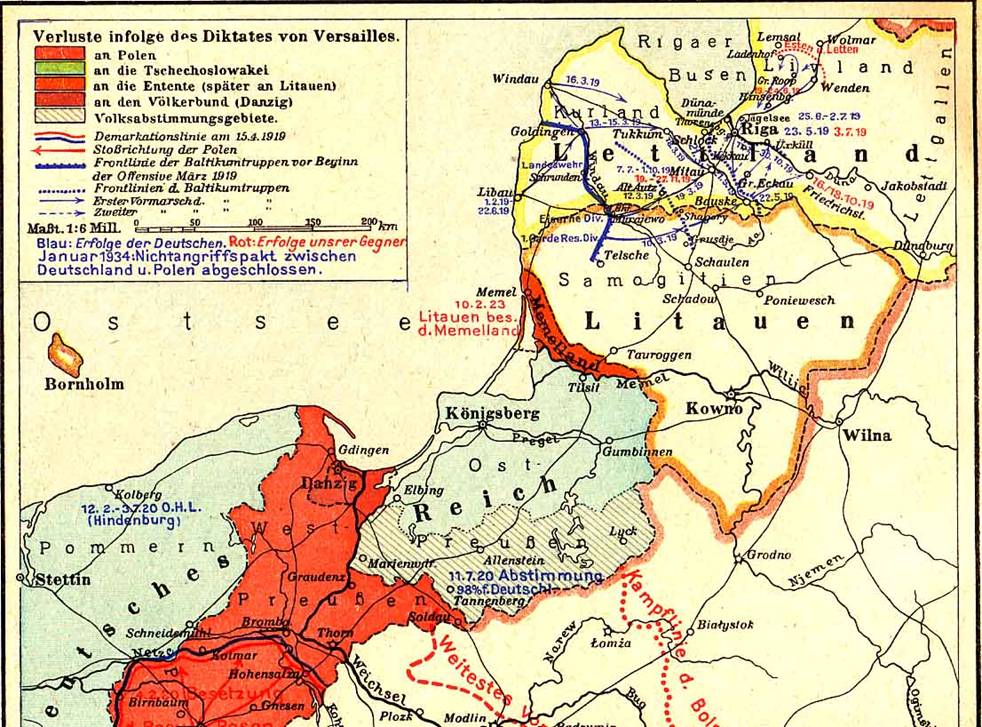

In June

of 1919, in an effort to secure its southern border, Estonian national forces

were compelled to defend themselves against two groups; the Landeswehr, a

Baltic German military force, and the Iron Division, which was made up of Baltic

and Reich Germans led by General Rudiger von der Goltz. (Raun,

p. 109) In the Landeswehr War, as it was refered to, and under the guise of fighting Bolshevism,

Von der Goltz attempted

to takeover the Baltic, but was nevertheless

defeated in a short, yet bloody battle, by the Estonians. Click on the map to

see the details The

ambiguity of power left behind by Ober Ost created an opportunity for many competing political

groups in the area. With the defeat of In The

tables began to turn in Almost a

year later, on December 13, 1919, Lithuanians pushed the last of the Freikorps into

BIBLIOGRAPHY; Chayesh, Anatolii, LitvakSIG,

Chicago, IL, [On the Front Line in Lithuania, 1915], 2002. http://www.jewishgen.org/litvak/1915fline.htm (May 28, 2002) This site contains 25 eyewitness accounts of German and Russian

occupation in various Lithuanian villages during WWI. They describe their

treatment by their occupiers as well as their feelings towards them. Department of History Map Library, [Maps of the World War I], n.d. http://www.dean.usma.edu/history/dhistorymaps/WW1Pages/WW1ToC.htm (May 20, 2002) Provides 52 maps of various stages of the war, from the western front

to the eastern front. Begins with the eve of the war in 1914 and ends with

the political realignments in 1919. Map #40 shows Hutier’s

offensive in September 1917, a battle in Greene, Warwick. Letters of Mifflin, 1931. This primary document is a compilation of the letters of http://www.karamuzejs.lv/en/ekspozicijas/1kars_e.htm (May 28, 2002) This site provides information on Kirby, David. The Baltic World 1772-1993. In Kirby’s second volume of the History of the Baltic, he disputes the

idea that the many reforms, revolutions, and rebellions of the time were

brought about by actions by the outer rim of society. Kirby argues that Liulevicius, Vejas. Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 2000. This book tells of the German army’s experience on the Eastern front,

and explains how radically different it was from the Western front. It also

describes how the primitiveness of the East led to the “demondernization”

of the Eastern front, as technology was not as important there as it was in

the West. There are also a number of wonderful maps depicting the changing

borders and front lines of Mawdsley, Evan. The Russian Revolution and the Baltic Fleet. Macmillan Press Ltd., 1978. Mawdsley argues that the slight attention that has been paid to the Baltic

region has had too much focus on the leadership of government and political

parties, and not enough on the ‘grass-roots’ of the area. While he does

examine the developments at the center, Mawdsley

also looks at provincial areas. The book continues past the end of the war

into April 1918, discussing what he calls the real end of the ‘pre-soviet’

Baltic Fleet. Tschischwitz. The Army and Navy During the Conquest of the October 1917. Press, 1931. This primary document written by then Chief of Staff of the German

Expeditionary Corps, Lieutenant General Von Tschiswitz.

He goes further than just retelling his experiences and also analyzes his

enemy –The Baltic Fleet’s- strategies and defenses. He compiles them into 24

descriptive chapters along with 16 sketches of the Baltic area in different

stages of the war. Originally

published at http://depts.washington.edu/baltic/papers/

|